“How do you handle cleaning up toys for a three year old? Or should I not have this expectation? My husband asked my three year old to pick up toys and she said, “No thanks”. So he said he would take something away if she did not do it. I don’t agree with this and my three year old doesn’t care! She says, “Go ahead”. At what age do we start cleaning up together and asking for /expecting participation? And what should the consequence be if they don’t/ won’t do it?”

It is such a common question, so today, I am going to offer some ideas originally shared in the Facebook group, RIE: Raising Babies Magda’s Way that may be helpful in thinking about how to approach this dilemma in a respectful way. Begin by understanding that living with young children means living with some (Okay, sometimes a lot of) mess. Learning, growing, playing, and creating is a messy affair. Letting go of the expectation that your home will be Pinterest perfect goes a long way. As with most things, encouraging cooperation and participation in cleaning puts the onus on us as parents to do most of the “heavy lifting” in the early years. It takes time, modeling and patience, and we have to try to see through the eyes of our children.

It can be very helpful to create a yes space” within your home, which is essentially the child’s play space, and that way, toys are confined to one area. It can also be helpful to have baskets for easy sorting and cleaning up. But aside from these practicalities, it is important to build the habit and to invite, rather than insist upon or force cooperation, and this can begin at a very young age. During parent/infant education classes, I bring a large basket, and five to ten minutes before the end of class, I bring out the basket and very slowly begin to collect the toys, narrating what I am doing. This is a signal to the children that the class is drawing to a close, and we will soon be saying goodbye. I ask parents to remain seated and to stay relaxed as I gather toys. By the time children are young toddlers, when I bring the basket out, I usually have several eager and willing helpers. I usually pick up just a few toys, and then sit and let the children bring toys to me. I don’t expect or direct them to help, I don’t sing a clean up song, and I don’t make a big deal of it if some children choose not to participate.

Likewise, at home, I began a similar routine with my girl when she was an infant. I would tidy her play area twice a day, usually midday and early evening. For a long time, she just watched, then she liked to “help” by taking toys out of the baskets, and then one day, when she was about two, this happened:

I would generally just start and let her join in any way she wanted to. At age two and a half, she eagerly participated in cleaning up. She had started to build these tall block towers, and I would always ask her if she’d like to leave them or if she’d like to knock them over and put them away and rebuild them later. Engaging her in the process and seeing clean up as a “wants something” caregiving time, and a cooperative effort was important. A good rule of thumb for both younger and older children is to not allow access to more toys than YOU are willing or able to pick up all by yourself. This does not have to be a battle. Children don’t need to be threatened with consequences, manipulated or bribed in order to participate in this process.

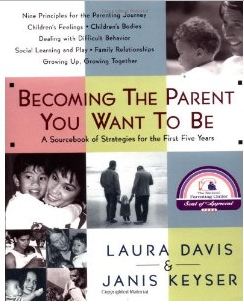

Janet Lansbury adds: “Children are more likely to help out when they don’t feel pressured or on the spot, aren’t too tired, and have been approached with a positive, polite attitude. When we don’t give them a ton of these kinds of rules and we stay on their side, they feel genuinely loving towards us, and want to help. I would only ask in the most open way, “Would you mind popping some of those blocks into this bucket?” If she says no or just doesn’t do it, keep going yourself, maybe asking her again with something else. If you ask children any question, it has to be okay for them to say no. What I’m saying is to stop trying to find an approach to get her to do this. Ratchet this all back to being perfectly willing to pick up yourself. My advice would be to put out less stuff if you don’t want a big mess to clean up. You can’t force these things. You can’t force someone to like and respect you. That’s a kind of old-school thinking that leads to punishment and a less intimate and trusting long-term relationship between parent and child. Yes, a child may be perfectly capable of cleaning up, but that will always be a voluntary activity on her part. You cannot force this, unless you want to resort to punishment and creating more of a divide between you. Being capable and wanting to do it are two different things. From my point of view you are trying to straitjacket her into being more mature than she is and that always backfires, because we don’t get what we want in the end. We might get a “good” child that feels a lot of shame inside and doesn’t feel particularly intimate with her parents.”

Kate Russell, of Peaceful Parents, Confident Kids, echoes Janet’s advice, saying, “Children are inherently good, kind and helpful. They don’t need to be taught to be these things. When children are able to act these qualities out it is because all their needs are met. They are feeling safe, supported, trusted, accepted, loved, connected. They aren’t hungry, tired, overwhelmed, overstimulated, etc. When you get annoyed or frustrated with your child for not following your orders, you undermine her feelings of safety, support, acceptance and love, and therefore it is nearly impossible for her to naturally and authentically want to help or follow your orders. I would encourage parents to explore further where these ideas that children must experience consequences for not complying are coming from. Often, it’s related to our own upbringings and values we had forced on us early on.”

Finally, Shiva, mom to a four year old, reflects, “Last night I found myself a bit frustrated about my child’s lack of participation in cleaning up before bedtime so I took the time to search for some guidance. After reading the comments above, the first thing I did this morning was to declutter and put some of her toys away (with her input). I slightly shifted my perspective and tone during our clean up routine tonight and noticed a huge difference! We also started cleaning up a little earlier than usual to ensure that she’s not too tired, and I set some limits, telling her if she’d like to play with her toys that she needed to make sure they stay in her room.”

So, what do you think? Are you ready for a shift in how you approach clean up with your children?