For your consideration and discussion:

Santa Cruz parenting classes, parenting workshops, and early childhood education

He isn’t a baby anymore. He’s growing in leaps and bounds, and scaling new heights every day, in every way. As his world grows larger and he begins to play with other children besides his sister (who has been the world to him up to now), both the physical and the emotional challenges he faces are bigger. At the park last week, J. worked and worked, and was finally able to scrabble up the “big” rock. He sat at the top, next to B. (a little boy we know from our neighborhood, who at almost four years old, is about a year and a half older than J.).

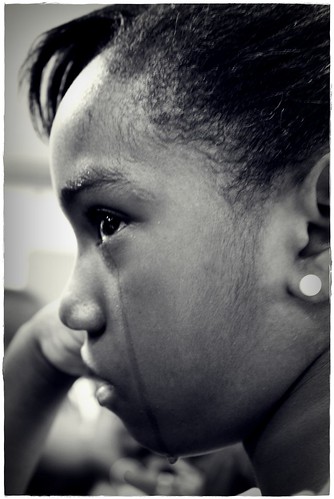

B.’s Mom and I were standing nearby, chatting. Suddenly J. was falling, and he landed face down on the ground next to the rock. I quickly moved in close, and J. lifted his arms to indicate he wanted me to pick him up, while emitting a heartrending sob. I held him close, and gently rubbed his back. I could feel his chest heaving against mine. I wanted to take a look and make sure he wasn’t bleeding anywhere, but he was clinging to me tightly. In between sobs, he choked out these words – “B. p…p…p…pushed m…m…me!” I could hear the shock and bewilderment in his voice. I understood that while the fall may have hurt, the fact that he had been pushed by a friend hurt more.

In that moment, I felt my stomach clench, and a flash of anger ran through me like a current. My thoughts went something like this: “Why???would B. push J.? How could he? J. is one of the most gentle children I know. He was just sitting there! B. is older- he should know better. How would he like it if someone (like me) pushed him off the rock?” (I know, I know- I’m supposed to be a professional. I’m supposed to know and understand that these things happen, that it’s all part of life and learning, and that both children are in need of compassion. And I do know it, and I practice it.) But in that moment, it was my J. that was hurt and sobbing because another child had intentionally (and stealthily) pushed him.This was the first time something like this had happened to J. in the two and a half years I’d been caring for him. Somehow, in my heart and mind the fall was worse because someone else had purposely caused him to lose his balance. I felt protective- a little like a Mama Bear maybe- “Don’t even think about hurting my baby or I’ll hurt you!” But it turned out J. didn’t need my protection, as evidenced by what happened next.

B.’s Mom had heard what J. had said, as had B., who had made a quick exit from the scene. As I continued to comfort J., B’s Mom brought him back over to where we were, and asked him if he had pushed J. She was clearly upset and flustered. She was both apologizing to me and telling B. he had to apologize to J. B., meanwhile, wouldn’t look at her, and was trying to squirm away. I was still holding J., who indicated he wanted to get down. Still hiccuping, he walked right up to B., looked him in the eye, and very clearly said, “B. don’t push me! I not like it! You not push me again!” B.’s Mom insisted B. had to apologize to J., and B. offered a halfhearted, “I’m sorry,” but J. had said what he had to say, and he wasn’t holding any grudges. He was ready to go back to playing. “Come on B.! Want to climb the rock?” Fifteen minutes later, when it was time for us to leave the park, J. was happily waving and calling, “Goodbye B.! Bye, bye! We see you soon.” I spent the last fifteen minutes at the park reassuring B.’s Mom, who was distraught that this “problem with pushing was coming up again.”

I stood humbled and in awe of J., who, at two and a half years old, demonstrated an ability to clearly express his feelings and boundaries, while navigating a difficult situation with grace and forgiveness, which is something I sometimes still struggle to manage to do easily. Young he is, vulnerable he may be, and certainly he needed the comfort of my arms, and my listening ear when he had been hurt, but how amazing to realize his ability to negotiate a friendship on his own terms. I wonder why it’s so hard for us “grown-ups” to do the same?

Is it hard or easy for you to let your child take new physical or emotional risks? What feelings come up for you when your child is hurt? Are the feelings the same or different when the hurt is caused by someone else’s actions? How much do you think adults should intervene in children’s interactions or conflicts?

Structure, expectations, predictability- all add up to responsibly raising and loving our children. The freedom we all feel deep within ourselves comes once we understand where we stand in the scheme of things.” Magda Gerber

From my mailbox:

“I am 23 years old and have a 3 year old daughter and a 3 month old son. I just recently began researching alternatives to corporal punishment and have come across so much information I am having a hard time sticking with one particular style. I’m trying to pick and choose what I feel is right but it seems that everything I have tried with my little girl isn’t doing much so I revert back to yelling and spanking and threatening corner time. It really really hurts me to treat her that way but that is how I was raised and I am having such a hard time breaking the cycle. Her most used lines are “I don’t want to.” “NO!” “I said NO!” Where do we begin?”

“I don’t know what to do when my son does something to hurt his little sister, like hitting, kicking, or grabbing a toy from her. When I see my son act like this, I feel angry at him, and protective towards the baby. I want him to learn to be kind and gentle with his sister, and I don’t understand where this behavior comes from. We are always gentle with him.”

“I’m a single Mom, and sometimes, my daughter just wears me out. I feel like I’m saying the same things again and again, and she just doesn’t hear or listen. After the tenth time of saying “No!” or asking her to do something, sometimes I just lose it and yell at her, especially at the end of a long day, when I’m tired too.”

“Mornings are the worst for me. It’s always such a busy time. I’m trying to get all of us dressed, fed, and out the door on time, with everything we need for the day, and that’s always the time my youngest chooses to have a meltdown, or cling to my leg. I try to stay calm, but it’s hard. He will be throwing his breakfast on the floor, refusing to get dressed, or chasing the poor dog and pulling her tail, and I just don’t feel like I have the time to deal with it calmly.”

“How do I deal with it when my daughter screams at the top of her lungs, no matter what I say or do?”

“My son is 18 months old and he loves to throw balls and play catch. The problem is he throws everything, and often at someone, and sometimes hurts them! How do I teach him (or can I, at his age) what’s appropriate to throw, and where?”

“I have trouble getting my son to look me in the eye when he’s bitten me or his father. And I’m speaking about when he bites for sport / play, not when he’s tired, overstimulated, etc. Traditionally, when he’s bitten us, I simply and neutrally state “No biting” or “I don’t want you to bite” and then move on so I don’t fuel the fire with attention. But over the past few months, this has stopped working. So, I’ve instead started kneeling at his level and tellling him gently that I don’t want him to bite me. It’s at these times that he’s squirmy, looks away, and deliberately avoids eye contact. Any ideas? Or is this the wrong technique? He’s 23 months, by the way.”

Does any of the above sound familiar? All of the toddlers in these examples are acting in completely normal and age appropriate ways, but their behavior can sometimes be perplexing and exasperating to the adults who love them, and it can be hard for parents to know how to respond. We want to help young children to learn to behave in socially positive ways. Young children need to trust we will respond with kindness, and help them to understand the limits and learn what behavior is expected and accepted. Recent research indicates that if we react with harshness, young children can’t learn anything at all. Young children feel safe and secure, and can cooperate more easily when adults calmly set clear, consistent and firm limits, when the “rules” don’t change, and when they are told what they can do instead of just hearing “No!”

Here are five easy steps to help you effectively (and calmly) set limits with your toddler:

1) Begin with empathy and trust. Assume your toddler is doing the best she can do in any given situation, and is not just trying to drive you crazy. Trust this: with your gentle guidance and some time, he can and will learn to act in more positive ways.

2) Next, observe or notice what is happening, and simply narrate or state what you see or hear.

“You hit your sister, and she is crying.” “You are throwing the sand.” “You are throwing your food.” “You are screaming.” “You are throwing your blocks.” “Ouch, you are biting me!”

3) Briefly explain why you want the behavior to stop.

“It hurts your sister when you hit her.” If you throw the sand it might get into someone’s eyes, and that hurts.” “Food is for eating. It makes a big mess when you throw your food, and I don’t like it.” “It hurts my ears when you scream,” or “I can’t understand you when you scream.” ” Blocks are hard and it might hurt someone if you throw blocks at them.” “Biting hurts.” Notice two things: Most of the time, you want or need to set a limit when your child’s actions might harm them or someone else. Also, it is perfectly acceptable to ask your child not to do something because you don’t like it- your feelings and needs matter. So if you find yourself getting upset because your child is making a big mess that you will have to clean up, or you just can’t bear to listen to another moment of screaming, say so! Sometimes just drawing attention to the behavior and the reason it is inappropriate is enough to stop the unwanted behavior (at least in the moment).

4) Set the limit, while demonstrating the desired behavior or offering an alternative, if possible.

“I won’t let you hit your sister. Please touch her gently.” ( Say this while stroking both children gently.) “If you want to hit, you can hit this doll (or the floor, or these pillows).” “Please keep the sand low in the sandbox” ( demonstrate). ” If you can’t remember to keep the sand low, I’m going to ask you to leave the sandbox.” When you throw your food, that tells me that you’re done eating. If you still want to eat, please keep your food on the table or I will put it away (or ask you to get down).” “Please don’t scream. I want to understand, and I can’t when you’re screaming. Can you show me (or, tell me using your regular voice) what you want?” or “If you want to scream, I will ask you to go in the other room (or outside).” “If you want to throw something (or play catch) let’s go find a ball. Balls are for throwing. If you keep throwing the blocks I will put them away for today.” “No biting!” ( Say this firmly, while putting your child down.) I will move away if you are going to bite me. If you want to bite, you may bite this teether.”

5) Follow through with the limits each and every time (consistency). This is very important.

When you set a limit your child may resist, or express some angry or sad feelings. This is perfectly natural, and fine. Accept, name and acknowledge your child’s feelings, but calmly hold firm to the limit. Your child is entitled to express and have her feelings heard, but that doesn’t mean you have to meet her anger with anger, agree with her, or give in to him.

Help your child if necessary. Stay nearby and supervise closely if your child is prone to hitting his sister. “You are having a hard time remembering to keep the sand low in the box, so I’m going to ask you to leave the sandbox now. Can you do it yourself, or would you like some help?” “You are still throwing your food. I’m going to put it away now.” (You can also hand your toddler a cloth and ask her to help you clean up the food that was dropped.) “You are still screaming. I’m going to ask you to go get all your screams out in the next room,” or “I can’t help you when you’re screaming.” “I’m going to put these hard toys away, and you can play with these balls and stuffed animals.” (In some cases, it may be necessary or helpful to make changes in your environment or routine that will make it easier for your child to remember and cooperate with the limits. For instance, it may be helpful to put away hard toys for awhile if your child is intent on throwing everything. Maybe providing a gated, safe play area for the baby will protect her from her brother when you can’t be right there to intervene. Maybe changes in the morning routine are needed to make it a less rushed, stressful time, or you can put aside some special toys that come out just in the morning for your toddler to play with.)

Remember, the attitude with which you approach your child and the tone of voice you use when setting a limit matters just as much as what you say. The goal is not to punish, but to teach. Children learn just as much (or more) from what we do, as they do from what we say. Magda Gerber always said, “What you teach is yourself.” What do you think she meant by that?

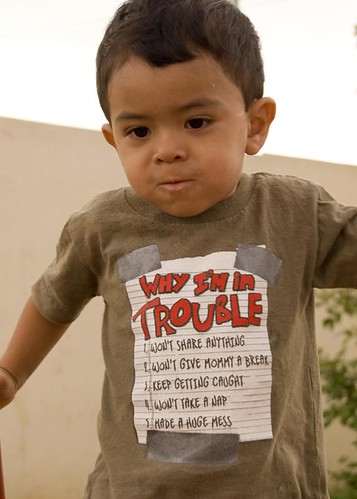

Toddlers may not be able to say many words, but they can sure let us know how they feel about all those people who keep telling them what to do. “No!” “Not now! “Go Away!” (From 1, 2, 3…. The Toddler Years: A Practical Guide for Parents & Caregivers)

The Central Coast Early Care and Education Conference took place this past Saturday at Cabrillo College in Aptos. I was particularly excited to attend a workshop given by Sandy Davie, Nora Caruso, and Sharon Dowe of the Santa Cruz Toddler Center. The Toddler Center was founded as a non-profit in 1976, by two working women who were concerned about the lack of quality care for very young children. The first of its kind in the Western States, the center’s philosophy and practice is based on Resources for Infant Educarers (RIE) , the program founded by infant specialist Magda Gerber.

It is always inspiring and uplifting to listen to and learn from others who are involved in and passionate about ideas and work similar to my own. One of the things I most miss about working in a childcare center is the collaboration with, and support of colleagues. It can sometimes be a little bit lonely and a little bit hard to be the sole adult at home caring for a toddler (and his sister) even though I have chosen this work and love doing it. ( My role as a nanny gives me great compassion and insight into the challenges parents face – especially stay at home Moms or Dads.)

Little did I know I was to have the opportunity to participate in an exercise that would serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of slowing down, and including the child I’m caring for in whatever is happening. Another workshop participant and I were asked to imagine we were one year old children playing happily together. (We were given a pad of post it notes as our toy.) All of a sudden, as I was happily crumpling the paper, and experimenting with the sticky strip, one of my “teachers” approached me from behind, and without any warning, tried to put my jacket on. She was talking to me loudly about hurrying up to get ready to go outside. I resisted her by turning away, and refusing to put my arms in the jacket. I glared at her, and told her “No”, but she insisted, saying I would be cold if I didn’t put my jacket on, and telling me she didn’t understand why I was being so difficult. I could tell she was frustrated with my resistance, but her frustration only fueled my fire. Then we stopped the role play and processed what had just happened. I can’t tell you how irritated I felt. I actually didn’t hear much of what my “teacher” was saying to me, so intent was I at fending off her unwanted ministrations. All of her talking just sounded like noise to me. The whole experience felt a little like having a mosquito buzz in your ear while you are trying to sleep.

Next, the exercise was repeated, but the “teacher” moved more slowly, came to me and made eye contact, and let me know that in a few minutes it would be time to get ready to go outside to play. I wasn’t surprised when she returned a few minutes later and told me it was time to put away my toy and get ready to go outside. She explained it was cold outside, and she thought I’d be more comfortable if I wore my jacket. She gave me the choice of getting the jacket from my cubby by myself, or going with her and doing it together. She asked me if she could help me put my jacket on, before continuing. This time, I understood what was happening, and what she was requesting, and it was easier for me to cooperate with her. But something unexpected happened. When my “teacher” went to zip my coat, I suddenly had a strong urge to resist. I wanted to do it myself! I stepped back, and pulled the zipper from her hands. She understood, and acknowledged, “You want to try to zip your jacket by yourself.” She then let me spend a few minutes trying to zip the jacket before asking if she could help me by starting the zipper for me. What a different feeling I had inside this time!

Fast forward to today. It started raining just as J. and I were about to walk out the door to pick up his sister from school. We were running a few minutes behind due to the fact that he had slept a little later than usual, but since we were walking, I had to stop to get his rain jacket. I was feeling a little rushed, and was grateful when J. happily cooperated with putting his jacket on. But, as I reached to zip the jacket, he stepped back and said “No Lisa, I do it myself.” My first impulse was to tell him we didn’t have time, and I would do it for him, and he could do it next time, but suddenly I just stopped, took a breath and said “OK, you try.”

In the moment J. stepped back, I had a flashback to Saturday, and I literally felt, in my own body, J.’s absolute need to try to do the zipper himself . I waited quietly while he tried once, twice, three times. He narrated, “I can do it.” “Hey almost.” “It goes here,” as he tried to fit the two pieces of the zipper together. It felt like a long time to me, but it was actually only two minutes. When he looked up at me, I gently asked, “How about if I start it for you, and you can finish zipping it?” He nodded, and so I bent down, and fitted the two pieces together, and he zipped the jacket easily. He broke into a huge grin, and he pulled himself up tall. The message was clear- he felt satisfied and proud of himself. He took my hand and we set off for school together.

Have you guessed the secret to turning a toddler’s “No!” into a “Yes!” yet? My willingness to step back and wait for J. to try to zip his own jacket most likely avoided a power struggle between us. So many times, my ability to just let go, and wait a minute (or not) determines whether or not a struggle will ensue. I admire J.’s strong spirit, his fierce independence, and his desire to try things for himself. And the experience I had on Saturday reminded me of just how important it is for me to slow down, and give him the time and the respect of allowing him to participate fully in whatever we’re doing together, as often as possible.

Magda Gerber asked us to “look at babies with new eyes,” and consider what it means to treat a baby with respect. Her suggestion to treat a baby with the same respect we’d treat an “honored guest” is still not widely understood or practiced by most.

In Always A Bundle of Joy, (at Positive Parenting: Toddlers And Beyond) the author asks, “Do you think all the labels we have pinned on young children, such as “brats” and “terrible twos” and “tyrannical threes” may have distorted our lens through which we view them?”

I think if you are a parent, caregiver, or teacher of young children, the way that you parent, care, or guide, is governed by (sometimes unconscious) beliefs you hold about the children in your care. Even parents who claim to eschew parenting philosophies and follow their instincts, are acting out of underlying beliefs about what they think young children are like, and what they need.

This is why I begin almost every workshop I do by asking parents, caregivers, or teachers to complete a few simple sentences: Babies are _____________. Babies need _______________. Toddlers are _____________. Toddlers need ____________. I ask workshop participants to spend about ten minutes completing this exercise, writing down the first ideas that come to mind. We then go around the room and share our answers. Generally, this leads to a lively discussion, and people are often quite surprised to discover their own biases, and how strongly their beliefs impact their approach to caring for and interacting with children.

If we change our beliefs, we change the way we act. If we change the way we act, we change the outcomes we get. It’s as simple as that. Even when we can’t change the outcome immediately, the way we think about what’s happening can lead us to a more (or less) powerful, peaceful place from which to respond. (For instance, babies cry, and sometimes we don’t know why, nor can we easily soothe them. Depending on our beliefs about why a baby cries, what the cry means, and what a crying baby needs, we will respond in different ways and more or less calmly, even if we can’t easily soothe the baby.) I’ve been reflecting on this simple truth lately, and have been collecting some words of wisdom to inspire me in my daily work with children. I’d like to offer the following as food for thought:

There are hundreds of different images of the child. Each one of you has inside yourself an image of the child that directs you as you begin to relate to a child. This theory within you pushes you to behave in certain ways; it orients you as you talk to the child, listen to the child, observe the child. It is very difficult for you to act contrary to this internal image. For example, if your image is that boys and girls are very different from one another, you will behave differently in your interactions with each of them.

The environment you construct around you and the children also reflects this image you have about the child. There’s a difference between the environment that you are able to build based on a preconceived image of the child and the environment that you can build that is based on the child you see in front of you – the relationship you build with the child, the games you play.

Yesterday, I came across this quote that is so profound, I want to share it in its entirety here:

when we adults think of children, there is a simple truth which we ignore: childhood is not preparation for life, childhood is life. a child isn’t getting ready to live – a child is living. the child is constantly confronted with the nagging question, “what are you going to be?” courageous would be the youngster who, looking the adult squarely in the face, would say, “i’m not going to be anything; i already am.” we adults would be shocked by such an insolent remark for we have forgotten, if indeed we ever knew, that a child is an active participating and contributing member of society from the time he is born. childhood isn’t a time when he is molded into a human who will then live life; he is a human who is living life. no child will miss the zest and joy of living unless these are denied him by adults who have convinced themselves that childhood is a period of preparation.

how much heartache we would save ourselves if we would recognize the child as a partner with adults in the process of living, rather than always viewing him as an apprentice. how much we would teach each other…adults with the experience and children with the freshness. how full both our lives could be. a little child may not lead us, but at least we ought to discuss the trip with him for, after all, life is his and her journey, too.”

– professor t. ripaldi

Finally, Janet Lansbury offers this insight borne out of her experience:

One of the most profound lessons I’ve learned since becoming a mom– reinforced by observing hundreds of other parents and babies interact — is that there is a self-fulfilling prophecy to the way we view our babies. If we believe them to be helpless, dependent, needy (albeit lovely) creatures, their behavior will confirm those beliefs. Alternatively, if we see our infants as capable, intelligent, responsive people ready to participate in life, initiate activity, receive and return our efforts to communicate with them, then we find that they are all of those things.I am not suggesting that we treat infants as small adults. They need a baby’s life, but they deserve the same level of human respect that we give to adults.

What do you think? Do you think the image we hold of a child makes a difference in how we treat them? Do you think children “live into” our expectations (even if they are unspoken)? What images do you hold of babies and toddlers? What labels do you assign to them or to their behavior? Do you have any favorite quotes to share about the way we see children, and how our thinking might guide our actions, and impact the response we receive? I’d love it if you’d share!

One of the things I appreciate about social media is the opportunity to connect with so many wonderful people, and to learn so much from them. One of the ways I connect and learn is through participating in chats on twitter. There are chats on any number of subjects on any given day, and each chat has it’s own purpose and feel. Chats can range from light and informal, to serious and educational. All chats provide a great opportunity to network, and interact with a number of others who have an interest in the same subject matter. #pschat is one I participate in on a fairly regular basis (as my work with children allows). It is hosted by the lovely Lela Davidson who is the author of Blacklisted From The PTA, and editor of the parenting squad site.

The majority of the women (and a few men) who participate in the chat are parents, and the topic each week varies, but it usually centers around a current “hot button issue” in parenting. The conversation is lively, and the tone is often lighthearted and funny, and I’ve made some lovely connections. Most of all, I enjoy “listening in” and hearing from parents regarding their honest thoughts on their parenting challenges and joys. As is my wont, I often play devil’s advocate and bring my own unique point of view to the arena.

This week, the topic and the conversation took a more serious turn than usual, as the discussion centered on a news story that has been making the rounds recently. The story is about Jessica Beagley, more commonly referred to as the “Hot Sauce Mom.” She lives in Alaska with her children, two of them adopted from Russia. In this segment, which aired on national television, and was filmed by her daughter, Jessica punishes her seven year old son for misbehaving at school and lying about it, by washing his mouth out with hot sauce, and forcing him to take a cold shower. Jessica is now being investigated for and charged with child abuse.

Needless to say, there were strong reactions and varying opinions on this topic, and the conversation quickly veered toward this general question: “What are effective ways to discipline children?” Everyone participating in the conversation seemed to agree that it is necessary to “teach” discipline, but there was disagreement as to the best approach, with some advocating for the use of “judicious” spanking, others for time out, some for consequences such as the removal of TV and computer privileges, and still others advocating for more gentle and respectful ways of instilling discipline.

It was clear that we weren’t all going to reach an agreement, but to me, that’s fine. What is important, as far as I’m concerned, is that the conversation is taking place. As my friend Suchada says, “The more people talk, the more the word is out there. It’s the only way change will happen.” One Mom, who is a believer in spanking as a form of teaching discipline, ended up asking those of us who believed discipline was possible without spanking for resources that gave alternative (effective) ways to discipline children. My final comment, which was passed on by many was this: “We’ve GOT to separate “discipline” from physical punishment, and shame. You can accomplish one without the other!”

Lela concluded with a question to me which inspired this post: ” How do you instill authority? Because at some point the kid has to STOP when you say so, instead of running in the street.” There is no answer to Lela’s question that can be given in 140 characters, which is what one is limited to on twitter. It so happens I wrote a series of posts on the topic a few years ago (before anyone knew I even had a blog). So, over the course of this week, I am going to share those posts, but I am also going to be writing some new ones on the topic, because this chat made me realize that I have more to say about disciplining children, and the story of the “Hot Sauce Mom” made me realize that parents really need (more) support and specific guidance regarding how to accomplish their goal of teaching children to behave in socially acceptable ways, without using physical punishment or shame.

My goal is to support families and teachers of young children to find ways to discipline that are both respectful to the child, and that work! I want to be clear that I’m not coming from a place of judgment, nor am I a (self proclaimed) expert. I believe people love their children, and do the very best they can as parents (even Hot Sauce Mom) given their own childhood and life experiences. I also believe that there are effective ways to discipline children that don’t involve using physical punishment, instilling fear, threatening disconnection, shaming, or intimidating them. Not only do I believe this, I know it to be true, based on my (ongoing) education, personal observation, and professional practice and experience.

Why am I so passionate about sharing this message, information, and resources for alternatives to physical punishment as a means to discipline? The answer is borne out of my own experience as a child. I was disciplined in very traditional ways: “Do as I say, not as I do.” “If you don’t follow the rules, you will be punished.” I was bribed to be “good” – “You won’t get xyz if you behave like that.” “You’ll get $5.00 for every ‘A” on your report card.” “You won’t get dessert if you don’t eat all your dinner.” “Why can’t you be more like your sister?” I was shamed, and told I was a “bad child,” when I did “wrong,” and I was hit with a wooden spoon for general “disobedience,” slapped across the face for being “fresh” and sassing back, and I had my mouth washed out with soap for saying bad words.

I am forty eight years old, and I still remember the pain (both emotional and physical) and the outrage I felt when these “punishments” were meted out. I both loved and feared (and sometimes hated) my parents. The message I received and internalized was this one: “I am inherently bad.” I learned to be outwardly compliant, and to cover my tracks and lie very well. (In fact, much to my embarrassment, I was voted “Best Alibi Artist” my senior year of high school.) I also learned to be dependent on outside evaluation, and to look outside of myself to decide how to conduct myself and how to live my life, as opposed to developing an inner moral compass to use as a guide. As I shared during the chat, the way my parents chose to discipline me… “may have kept me out of trouble as a kid, but kept me in therapy for most of my adult life.” (My brother and sister didn’t fare as well. My sister committed suicide at the age of fifteen. My brother is still alive, but lost to his addiction to alcohol and drugs.)

Please understand that I love my parents, and I know and believe that they love me. I understand they did their very best to raise me (and my sister and brother) in the only way they knew how, and the way they thought would ensure my happiness and success in life. This is not about blaming or bashing anyone- least of all my parents. In fact, I believe I have my parents to thank for leading me to study with Magda Gerber, and to my ultimate passion, which is the work I do to support children and families. I believe my experiences as a child have also helped to make me a less judgmental, more compassionate person, in general. (I’d just like to see more children get to where I am today, with a little more joy and ease, and a little less shame, and I’d like the same for parents!)

I’d like to end this post with two questions that I hope you will respond to, so that I can make the next posts I write as empowering and helpful to you as possible: 1) What is (or should be) the goal of discipline? 2) What is your biggest challenge, fear, or question when it comes to teaching your child discipline?

It seems ad executives are always dreaming up new ways to sell the same old thing; trying to capture a larger part of the market share. Diapers are big business, and it seems once parents have found a brand that works for them, they are pretty loyal to that brand, which can make it tough to convince them to try something new. I understand ad executives have got a job to do, and I don’t argue with their right to do it. A common way to sell consumers on something is to use humor, and to try to show them how buying a certain product or service will solve a problem they are having. I understand the approach, but don’t appreciate it when babies are perceived as the “problem,” and the humor comes at their expense.

Huggies brand (Kimberly Clark) diapers is at it again. They are launching a new ad campaign today to sell “Little Movers” Slip On Diapers-essentially a more absorbent “pull up” diaper, with Velcro tabs along the sides. These “new” diapers are intended to make it easier for parents to change wiggly, or active babies. It’s not the product I have a problem with, it’s the way babies are are referred to in the ad that I take exception to. The terms used to describe the “problem” babies? “Rolling Pins,” ” Acrobutts,” “Streakers,” and “Booty Scoochers.” The ad slogan? “Catch. Slip On. Release.” Chris Turner, a creative director at Ogilvy, who worked on the campaign had this to say about the slogan:

“At times, these kids can be like little wild animals and you just want to catch the little guy, quickly do your change, and then do your release. It really is just a more clever way of communicating ‘as easy as 1-2-3.’ ”

Really, Mr. Turner??? Little wild animals??? Simply a clever way of communicating ‘as easy as 1-2-3.’ ??? I pity your child. I’d like to suggest to you that human babies are not little wild animals, nor are they objects, and they don’t deserve to be made the “butt” of jokes by “clever” ad executives such as yourself . Further, diapering a baby should have nothing in common with fishing at all, as implied by the ‘Catch and Release’ campaign tag line.

Let me suggest that the “help” parents might need transforming difficult diaper changing times into more enjoyable experiences for both adult and baby, doesn’t come from the particular diaper they buy or use, but from the attitude and sensitivity they bring to the task at hand.

Magda Gerber had this to say about diapering:

How many times do you think a baby gets diapered? Six or seven thousand times. Why don’t we do it nicely? Why don’t we make it a learning experience? Why don’t we want a baby to enjoy being diapered? Diapering is very important. Diapering is sometimes viewed as an unpleasant chore… a time separate from play and learning. But in the process of diapering we should remember that we are not only doing the cleaning, we are intimately together with the child. We are all affected, negatively or positively, by cumulative experiences in our lives. One of the first such cumulative experiences is diapering, involving much of the child’s and parent’s time and energy during those first, most impressionable two to three years of the child’s life. While being diapered, the baby is close to the parent and can see her face, feel her touch, hear her voice, observe her gestures, and learn to anticipate and know her.

In How to Love a Diaper Change, Janet Lansbury gives tips for turning a diaper change into an enjoyable, connected time for baby and parent. I don’t know about you, but I think if I was a baby I’d appreciate being changed by someone who approached me with some sensitivity and respect, and saw and treated me as a person, instead of an object. I might be more able and willing to co-operate if I was included in the process, instead of having something done to me. I think babies pick up on, and respond to our attitudes and approach to them, and if we act like we are in a rush to get through an unpleasant chore, they may respond in kind.

Won’t you join me in defending and speaking up on behalf of babies who can’t speak for themselves? What are your thoughts on Huggies newest ad campaign, and Magda Gerber’s ideas about diapering babies with respect?

This left me speechless.

Names are an important key to what a society values. Anthropologists recognize naming as ‘one of the chief methods for imposing order on perception.’ ~David S. Slawson

Meet jeannezoo of zella said purple. In her own words, Jeanne is “an early childhood educator, artist, writer, book collector. committed to constructivist learning environments, documentation and photography as teacher research tools, and joy in the classroom.” Jeanne recently wrote a beautiful post entitled because it is your name , which inspired me to write this one.

In her post, Jeanne says,

KNOW that each name is important – the way it is pronounced and the respect it deserves.

The name IS the child that you are inviting, welcoming, and including into the family that is your classroom.

Uplift the names, uplift each child.

This reminded me of a conversation I once had with Magda Gerber about the importance of calling each child by their name. Magda felt that it was especially important for early childhood professionals (teachers, nannies, pediatricians, etc.) to address even the tiniest babies by their given names, as opposed to calling them by pet, or nicknames. To Magda, it was a question of respect. In our society, it’s still common for many, even professionals, to address both the very young and the elderly, using nicknames or pet names, which is disrespectful for two reasons; it both diminishes a person, and implies an intimacy and a power differential that should not exist.

As a teacher of young children, I’ve often witnessed that sometime around their second year, when toddlers are typically asserting their sense of individuality, they will insist on being called by their names, even by their nearest and dearest. Pet names won’t fly. Just last week, I was at the park and I overheard an exchange between two siblings. The big sister (maybe five years old) was comforting her little brother who had just taken a minor tumble from the slide. She sweetly offered to help him get up, asked him if he was OK, gave him a hug (which he returned) , and then she said, “I’m sorry my wee little sweetie fell and got hurt.” This seemed to offend and upset the little boy more than the fall had. He straightened up to his full height and indignantly declared: “I NOT wee sweetie, I Zwackery ( Zachery) !”

A favorite quote by Dr. Seuss comes to mind, “A person is a person, no matter how small.” And, I might add, no matter how young or old, and thus -deserves the respect of being addressed by his or her given name, instead of as “dear” or “sweetie” or “munchkin” or “baby” or “cutie”.

Because after all, our names are unique unto us, and define who are. I have many roles in my life- that of daughter, sister, student, teacher, caregiver, friend, lover, fiance – but I define myself to myself first and foremost by my name- Lisa.

Words have meaning and names have power. ~Author Unknown

For the same reason I try to avoid labeling children, or talking about them in their presence without acknowledging or including them in the conversation, I try to call each child I meet by their given name. Over the years, I’ve had the honor of caring for and teaching many children, and I remember each one of them by name.

Over time, I have also become very aware of how I am thinking about and describing children, both to myself and others. One day, a Mom who was frustrated with her young daughter was describing her as “clumsy, oafish, a little like a bull in a china shop.” I replied that I didn’t think of her that way at all. I thought of her as delightfully exuberant. Her Mom got tears in her eyes as she thanked me, saying, “You always seem to find and see the best in every child.” ( I try, but I’m not perfect, and I don’t always get it right.)

But doesn’t it make a difference in the way you feel about, and interact with a child if you use these words to describe his behavior:

“He knows his own mind, and is decisive. He needs my help to understand that sometimes others have different ideas and feelings about things.”

As opposed to using these words:

“He is obstinate and stubborn, and needs to learn that what he wants is not the only thing that matters.”

My favorite story about my name and my professional title? I’ve always felt there is no good name to describe my current chosen work – babysitter, nanny, caregiver- none of them feel quite right, or really fit. Magda Gerber came closest to accurately describing the work I do, when she coined the term “educarer” which could apply to either a parent or a professional- anyone involved in caring for a child or children on a day-to-day basis. The term embodies the notion that ” we educate (or teach) as we care, and we care while we educate.”

But in this case, I have to tip my hat to S., who is now almost six years old, and for whom I have been caring since she was just under a year old. When S. was three and a half years old, she started attending a preschool program a few hours a day, in the mornings. When I would arrive to pick her up every day, she’d inevitably be out back playing, and several of her little friends would run to find her, calling out, ” S, your Mom is here.” S. simply replied, “That’s not my Mom, that’s my Lisa,” which the other children seemed to understand, and accept immediately. And thus, I became known as “S.’s Lisa.” When S. started Kindergarten last year, she was thrilled to find another of her classmates had a “Lisa” too. The best job “review” I ever received? “Everyone should be lucky enough to have a Lisa like you.”

I’d love it if you’d share your thoughts with me about “the meaning of words and the power of names.”

Have you ever had an idea come to you out of the blue; an idea so obvious and simple, that you can’t believe no one has thought of it before? An idea you can’t wait to share with anyone who will listen, because you just know it will change the world for the better, and if not that, at least it can’t do much harm? Well I had one of those flashes today, and I am just itching to share, so here goes: I think this just may be the next “big thing” in parenting and educating babies and toddlers, the piece that has been missing and without which our babies and toddlers aren’t faring nearly as well as they might. Are you ready to hear what this missing piece is? It is simply this: We should be encouraging and teaching our babies to drive as soon as they are sitting up on their own. Just think about it for a minute before you dismiss my idea out of hand. Here are five good reasons to begin drivers education before your child is even out of diapers.

1) First of all, driving is a complex skill that most people will need to learn in order to survive and thrive in our industrialized, highly mobile society. So it makes sense to introduce your child to the basics early. You want her to grow familiar and comfortable with this tool she will be using for the rest of her life. The earlier you introduce her, the better. Of course, you aren’t going to just hand the keys over and leave her to her own devices; you’ve got to take it slow in the beginning. At first, you must always be present to supervise, guide, and interact. You can begin by just allowing your baby to sit in the driver’s seat, and let him practice playing with all of the various knobs and buttons so he can see what they can do. (I am, of course, writing a book, available soon on the e-reader of your choice, suitable for use by parents and educators. It will be full of suggested guidelines, lesson plans, extended learning opportunities, books and games, and so much more, all intended to help you make the most of this overlooked but wonderful learning tool that you no doubt have sitting in your driveway at this very moment.)

2) Which brings me to my second point: Cars are the ideal, interactive teaching and entertainment tools for young toddlers. Have you ever known a baby who doesn’t love to sit behind the wheel of a car, honk the horn, fiddle with the radio controls, turn the wipers on and off, shift the gears, and so on? Toddlers learn through hands on interaction with objects in their environment, and they are thrilled when their actions cause things to happen. What better way to provide hours of interactive learning (disguised as play) for your little one? Also, to date, your baby has been a passive on-looker, as she’s been strapped in a car seat in the back, and has had nothing to do but bide her time, and stare out at the scenery during long car rides. By moving her to the front seat, and letting her get her hands on all of these wonderfully responsive knobs and buttons, you are moving her into the realm of an active participant in her own learning.

3) Think about this too: As your child grows, and her interests and skills grow, so does the number and variety of activities she can do, using the car. She can learn to put the keys in the ignition, and turn over the engine, and as soon as she can reach the gas pedals and brake, she can actually take the car out for a spin. Steering, navigating, map skills, plotting a course, reading road signs, following the rules of the road, oh gosh- the possibilities for expanded learning are just endless. She may even become interested in car care, and maintenance and learn to understand the workings of an engine. Some children will even be designing their own prototypes by the time they’re in elementary school.

4) Again, with so many learning opportunities, doesn’t it just make sense to introduce the car early? It seems to me the earlier we start teaching our babies how to operate and care for a car, the better chance they will have at becoming proficient drivers at a much earlier age. And just think about how this might benefit you as a parent. No more endless hours spent in the car, ferrying children back and forth to school, to doctor appointments, lessons, playdates – what have you. By the time they’re about ten years old, children should be able to manage mostly on their own, and even arrange their own carpools. You can finally take a well deserved break, and they can feel the satisfaction of being able to get themselves to and from where they want to go- it will literally open up new worlds for them, at a much younger age than previously.

5) Finally, it’s time that we as a society stop underestimating our children, and what they are capable of. If we treat them like babies, incapable of understanding and mastering complex tasks, they will continue to act like babies. Times change, and the way we teach our children has to change with the times. Children will still have plenty of time to run around outside, and generally act like children, as long as we remember that we are the ones in control of the keys, and we limit the time we allow them to spend in the car playing and practicing their driving skills. But, if we are going to show our toddlers that we have any respect for them, that we believe in them and their capabilities, we’ve got to start giving them access to opportunities and tools that will stretch their horizons, at an early age. We don’t want them falling behind, do we? Besides, who needs toys when you can just hand your baby the keys to the car and make him happy for hours?

Now, I can imagine that there may be a few of you out there who are still unconvinced. Innovative ideas are always met with some skepticism and resistance at first, but I’m sure that this one is a winner. I’d love to have the opportunity to be the first to hear and reply to your concerns and questions. I have no doubt I can help to allay any fears or misgivings you may have, so please, comment freely and honestly.

(Now that I’ve convinced you all that I’ve gone completely nuts, go back and re-read this post, inserting the word “computer” wherever I’ve written car or driving. I wrote this post tongue firmly in cheek, after reading a tweet by Lisa Belkin, “Remember when toddlers used to be transfixed by your car keys? Ipad apps for Toddlers????” I thought, “Toddlers are better off with the car keys…” Most parents and early childhood educators would never think of handing a toddler the car keys, leading him to the car and saying “OK, here you go, have at it”, yet we might not think twice about handing a baby an iPhone or an iPad, for entertainment or learning purposes. There are marketers (no surprise), and there are even some early childhood professionals who advocate for the use of screen technology with our youngest children, but I can’t get behind this agenda. For a thoughtful exploration and discussion of the topic, you might want to look at this post at Childhood 101 , Why I don’t want to share my lap top (with my children. Additionally, this post , entitled the Mind/Body Problem, written by Susan Lin, of Commercial Free Childhood makes a compelling argument for why we should all be advocating for limits on screen time for young children. Susan’s post was written in response to NAEYC’s (National Association For The Education of Young Children) proposed technology position statement, which is being updated this year, and is meant to guide early childhood educators in the use of technology in early childhood classrooms. Technology is here to stay. Computers are wonderful tools- for adults. Children can and will learn to use computers, just as they learn to drive cars, and they won’t be missing out on anything by waiting until they are developmentally ready. I don’t believe they are ready until they are well out of their toddler years. In my opinion, children younger than say, the age of eight, have more to lose by engaging with screens, than they stand to gain. What are your thoughts?)